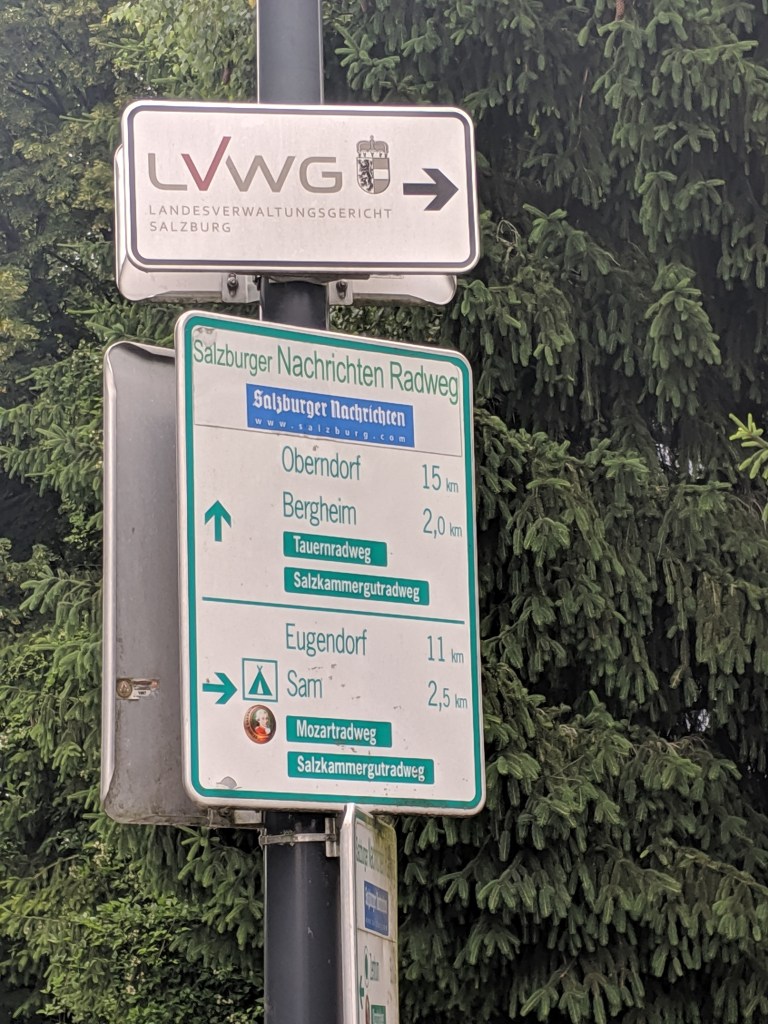

Leaving the Alps behind, we headed towards the Danube. When we were deciding on our route through Europe, this is the one section that I (Deb) really wanted to do. Mac wanted Verdun, France. Colburn wanted the beer route in Belgium. Lucia wanted to go to Prague. I wanted the Danube. Much like the EuroVelo 15 along the Rhine River, the Danube path (part of EuroVelo 6) has very low gradients, lots of infrastructure, and great opportunities to amuse the little ones with things other than biking. It’s perfect for a family interested in a bit longer ride. We originally had intended to bike this section of river in the spring of 2015 on our way back from Asia, but a combination of factors made it impossible at that point. We always said that we would come back and do it at some point, and this summer was our chance!

When planning our routes, we typically scour websites, guide books and tour company itineraries for ideas – both for what is interesting and what is possible. If a bunch of tour companies stop in a particular town for the night, the chances are that there is something interesting there and the infrastructure for tourists will be pretty good so we are likely to find a decent hotel or campground. They also tend to be very reasonable in what is able to be biked comfortably in a day. As we learned in our Guarda climb, sometimes the devil is in the details and the macro perspective needed to plan months of traveling can overlook key specific details. Using their knowledge makes our planning much easier, so we based our Danube route and timing on what the majority of the bike touring companies do for this section. With more than 600,000 people riding this section of the river each summer, the tour companies have plenty of experience with it.

More than five years after its inception, we were excited to finally on the Danube. Like a well-drilled army squad, we loaded the bikes, double-checked that we had enough food and water, and fell in to our typical riding order with Colburn in the lead setting the pace and doing navigation, Mac closely behind learning to modulate his strength so he can stay with the group, Lucia following him with her effortless perfect body positioning and me at the back to I can keep an eye on everyone. For most of our riding, we naturally fall in to this paceline – a single-file formation with less than a bike length between each person – because it is both easier to ride and takes up less space on the road or path.

As we rode out of Salzburg, I was admiring both our ability to function like this as a family but also in our new-found physical fitness. We were flying down the path. It felt amazing! Then it hit me. With a pit in my stomach, I realized that my desire to ride the Danube hadn’t taken in to account that the intervening years had dramatically changed our family dynamic and the past eight weeks had changed our overall fitness. We are no longer a typical family. It is the kind of thing you don’t see when you are immersed in it every day, but only when you can step back and look at it with objectivity. Lucia and Mac are no longer little kids on oversized bikes who need distractions, playgrounds and ice cream to make it through the day. As I found out when I was sick in France, they are now strong and capable adolescents experienced in the challenges of long, difficult, physical days and are even enjoying it as they learn more about what their bodies are capable of doing. In 2014 when we rode the Rhine, the kids could only ride 35-40 km per day both because of their attention span and physical ability. Four years later, we are doubling that on a regular basis and still done by early afternoon. Even the difference from just a few months ago is substantial. When we started this tour, we averaged, including stops, around 10-12 km/h. We are now able to average 22-25 km/h, depending on the terrain. This means that our 75 km day is around three hours of actual riding.

These changes, combined with our tendency to have a singular focus, led to some interesting on-trail riding dynamics. Our sister-in-law once commented, “Colburn and Deb, somewhere between a marriage and a task force!” and, I must admit, it is very true. We have, unfortunately, passed this on to our children too. For us, biking is no different – make the process as fast and efficient as possible. This became obvious to me on one particular day when Lucia, our extremely cooperative and non-competitive child, was leading the paceline.

There were a couple cyclists a few hundred meters in front of us when she picked up the pace. As our pace-setter, we simply follow her lead, so similarly sped up. As we neared the group in front of us, she geared up and quickened to a race-pace, sling-shots past them before settling back to a quick pace. “Wow, that was unusual for Lucia” I thought. A few minutes later it happened again – quickened pace to close the distance, gearing-up and race pace to pass, then slowing back to a quick pace to set the distance between. When it happened the third time, I realized that Lucia was doing this intentionally. We have now dubbed the process fishing for she casts her hook when she sees the group in front, reels them in with speed, then releases them back to go about their business without our interference once we have passed. Our non-competitive child most certainly is competitive on the path!

With most of our reservations made based on the 50-60km days that the bike tour companies suggest and not having the emotional energy to totally re-work the entire schedule, we had to adjust to a more leisurely pace of bike travel. The first few days we would make it to our destination before lunch and have a few hours to kill before we could even check in to our accommodation. In Mülheim, we went to a thermal spa and spent five hours swimming and having poolside drinks. Just outside of Linz, we stopped at a riverside pebble beach and spent a couple hours swimming and people-watching. Usually so focused on doing things and getting places, we sometimes forget to just enjoy the mundane. The slower pace changed this. Because there are only so many Baroque buildings, churches, and art one can admire before they all begin to look the same, we switched our focus to the more modern aspects of street art and food, even trying our hand at making our own (legal) graffiti in Vienna.

Once past Vienna, the bike tourist crowds thin substantially. While still a well-trod path, it is not over-run with cycle tourists making for some enjoyable days. The EuroVelo 6 continues all the way to the Black Sea in Romania but is much less developed outside of Austria. The paths are not as well marked and vary greatly in surface quality. What you get in exchange for the lower level of infrastructure is a much more genuine, friendly experience.

Almost without exception, the people we met were friendly, helpful, and seemed to be genuinely glad to see us. As we cycled our heavily laden bikes across a bridge one day, a woman walking the other way cheered us and gave each of us high-fives. While crossing a different bridge with a very narrow path for pedestrians and cyclists, each time we pulled off to the side between the girders to let the walkers pass we would receive a friendly köszönöm(thank you) for both young and old. In Mosonmagyaróvár, we saw a billboard for a small barbecue place so went there for lunch. As we stood in front of the menu, paralyzed because we could not decipher a single word on the menu but intrigued by the smells, the owner figured out that we don’t speak Hungarian or Slovak so quickly translated the menu, making us feel very welcomed and at ease. Their story of innovation and entrepreneurship is inspiring as they expand the types of food available in Hungary. If you’ve never had BBQ beef cheek, Más is definitely the place to try it! Similarly, in Komárno, our waiter/crepe chef welcomed us warmly to his city and made us feel as if we had just met up with a long-time friend.

The hospitality we received in both Slovakia and Hungary was wonderful, and a beautiful way to end of our journey. Eastern Europe is definitely a place where we would like to spend more time.

By the numbers:

- Distance cycled: a little more than 2,000 km (we didn’t keep track of everything)

- Crashes: 1 (Lucia clipped a tandem bike but no injuries)

- Flat tire/punctures/repairs needed: 1

- Countries visited: 10

- Baguettes, ham and cheese lunches eaten: too many to count!

- Major illness/injury: 1

- Bee stings: 5

- Butt blisters: 0

- Days spent sweating in >39C/100F heat: 6 (but many in the 35/90+ range!)

- Times we sang something from Sound of Music: ~ 50

- Times we said, “today was a good day” at the end: every day.

The bicycles are now dirtier, worn and yet still running smoothly despite our 1650km of trails, paths, roads, and sidewalks. The worn tires tell a bit of a story. It was in the Alps when we began to see the tires show the mileage and make us see just how far and over how many types of paths we are traveling. During our three-week trip through the region, the water fountains, train travel, and spectacular scenery were the constants of our time. Yet, it happened so quickly and now I am trying to recall the details of a unique area of Switzerland, the lower Engadine Valley in the ancient region of Rhaetia.

The bicycles are now dirtier, worn and yet still running smoothly despite our 1650km of trails, paths, roads, and sidewalks. The worn tires tell a bit of a story. It was in the Alps when we began to see the tires show the mileage and make us see just how far and over how many types of paths we are traveling. During our three-week trip through the region, the water fountains, train travel, and spectacular scenery were the constants of our time. Yet, it happened so quickly and now I am trying to recall the details of a unique area of Switzerland, the lower Engadine Valley in the ancient region of Rhaetia.

One of these elevation-days sticks in all of our memories – riding through Guarda. It’s not only memorable for the physical challenge and spectacular scenery but memorable for the cultural world we entered. The Romans had used this same path, the Via Claudia Augusta, through the Alps to get to northern Europe and if you are paying attention, you can see the influence everywhere you look.

One of these elevation-days sticks in all of our memories – riding through Guarda. It’s not only memorable for the physical challenge and spectacular scenery but memorable for the cultural world we entered. The Romans had used this same path, the Via Claudia Augusta, through the Alps to get to northern Europe and if you are paying attention, you can see the influence everywhere you look. Leaving St. Moritz, we entered another country it seemed; this was the Lower Engadine valley, a remnant of the ancient state of Rhaetia where Romansch is spoken. The Romansh language is another remnant of the type of Latin spoke by the common people of the Roman Empire. It’s spoken by 50-70,000 Swiss and is one of four national languages of Switzerland and seems to be a mix of them all. In this area, you would hear it on buses, at the market, at restaurants, and on the bike path. The paintings which adorned homes, especially in Scuol and Guarda, were unique and clearly influenced by Roman history. Earliest house decoration date from the 11thcentury but became common in the 16thcentury. An example of sgraffito might include fishes, fanciful beasts, suns, stars. This is a region where folk artists centuries ago displayed their craft through furniture but also exterior walls. In addition to patterns and pictures, there are often texts in Romansch.

Leaving St. Moritz, we entered another country it seemed; this was the Lower Engadine valley, a remnant of the ancient state of Rhaetia where Romansch is spoken. The Romansh language is another remnant of the type of Latin spoke by the common people of the Roman Empire. It’s spoken by 50-70,000 Swiss and is one of four national languages of Switzerland and seems to be a mix of them all. In this area, you would hear it on buses, at the market, at restaurants, and on the bike path. The paintings which adorned homes, especially in Scuol and Guarda, were unique and clearly influenced by Roman history. Earliest house decoration date from the 11thcentury but became common in the 16thcentury. An example of sgraffito might include fishes, fanciful beasts, suns, stars. This is a region where folk artists centuries ago displayed their craft through furniture but also exterior walls. In addition to patterns and pictures, there are often texts in Romansch.

Just meters from exiting the second tunnel and finding the top of the hill was the restaurant. The chalkboard out front said geöffnet, open. We entered the small courtyard looking like rabbits who have just outrun a fox, but the two women, likely friends, welcomed us warmly in German. We shared some words in German and Romansch and they were surprised and delighted. It was a sunny quiet table for lunch with two kind women.

Just meters from exiting the second tunnel and finding the top of the hill was the restaurant. The chalkboard out front said geöffnet, open. We entered the small courtyard looking like rabbits who have just outrun a fox, but the two women, likely friends, welcomed us warmly in German. We shared some words in German and Romansch and they were surprised and delighted. It was a sunny quiet table for lunch with two kind women. Leaving the cool of Ireland behind, we boarded an overnight ferry to France then had to take two trains to get to our starting town in France, Mauberge. As I mentioned in the Ireland post, getting on and off ferries and trains is a very stressful situation for bicyclists, and this was no exception. We were, however, able to make it through the process and truly enjoyed the open borders policy for the Shengen Area. Unlike the land border crossings we did in Africa, we simply continued our trip as if we were moving from county to county or state to state.

Leaving the cool of Ireland behind, we boarded an overnight ferry to France then had to take two trains to get to our starting town in France, Mauberge. As I mentioned in the Ireland post, getting on and off ferries and trains is a very stressful situation for bicyclists, and this was no exception. We were, however, able to make it through the process and truly enjoyed the open borders policy for the Shengen Area. Unlike the land border crossings we did in Africa, we simply continued our trip as if we were moving from county to county or state to state. Originally we were going to ride the EuroVelo 6 – a long distance cycling route (a bit more than 2,200 miles) which goes from the Atlantic Ocean in Nantes, France to the Constantia, Romania on Baltic Sea. As we researched the route, however, we found that it spent about a third of its time in France alone and missed most of the Alps, only skirting by some of the more northern parts. As mountain people, history nerds and lovers of beer more than wine, we chose instead to head to the north of France along the Belgian border. This would allow us to have more time with craft beers from some of Colburn’s favorite breweries, learn more about WWI and WWII by visiting Verdun and biking along the Maginot Line, and get to Switzerland and Austria before the crowds of July. This route also had the benefit of potentially being able to visit a few friends and family who are in the Netherlands/Belgium/western Germany area, so was a no-brainer.

Originally we were going to ride the EuroVelo 6 – a long distance cycling route (a bit more than 2,200 miles) which goes from the Atlantic Ocean in Nantes, France to the Constantia, Romania on Baltic Sea. As we researched the route, however, we found that it spent about a third of its time in France alone and missed most of the Alps, only skirting by some of the more northern parts. As mountain people, history nerds and lovers of beer more than wine, we chose instead to head to the north of France along the Belgian border. This would allow us to have more time with craft beers from some of Colburn’s favorite breweries, learn more about WWI and WWII by visiting Verdun and biking along the Maginot Line, and get to Switzerland and Austria before the crowds of July. This route also had the benefit of potentially being able to visit a few friends and family who are in the Netherlands/Belgium/western Germany area, so was a no-brainer. Because of our repeated ‘close calls’ biking in Ireland, we re-worked our route through France to take advantage of the myriad of bike paths and cycle routes which traverse continental Europe. This meant we had to change quite a few days as the automobile roads tend to take the most direct route but the cycling paths will follow old railway lines, quiet country roads, and be alongside meandering rivers to avoid the traffic and cut down on the elevation gains and losses. Several of our days went from 60-70 km to 90-100 km as a result. Despite the longer distances, the biking is so much less stressful that it is an easy trade-off. What we didn’t plan on, however, was that I caught a terrible GI bug in Ireland, cryptosporidium, that would take me down for almost all of our time in France. Sick, weak and dehydrated, I was barely able to function, never-the-less ride strong. The experience was so humbling for me I have written a totally separate blog about it – mostly so that it becomes part of our family history and we remember that not all of the traveling is sunshine and blue skies as it might seem from the outside and in our photos.

Because of our repeated ‘close calls’ biking in Ireland, we re-worked our route through France to take advantage of the myriad of bike paths and cycle routes which traverse continental Europe. This meant we had to change quite a few days as the automobile roads tend to take the most direct route but the cycling paths will follow old railway lines, quiet country roads, and be alongside meandering rivers to avoid the traffic and cut down on the elevation gains and losses. Several of our days went from 60-70 km to 90-100 km as a result. Despite the longer distances, the biking is so much less stressful that it is an easy trade-off. What we didn’t plan on, however, was that I caught a terrible GI bug in Ireland, cryptosporidium, that would take me down for almost all of our time in France. Sick, weak and dehydrated, I was barely able to function, never-the-less ride strong. The experience was so humbling for me I have written a totally separate blog about it – mostly so that it becomes part of our family history and we remember that not all of the traveling is sunshine and blue skies as it might seem from the outside and in our photos. Our first days riding in France were a lovely change from the starkness of the Connemara. Our bike path took us along an abandoned railway line that is now a rail-to-trail. Green and lush with a cool dampness, the riding was glorious. We were serenaded by birdsong, rode through small rural towns with cobbled streets, and the surrounding fields were just showing the first signs of summer – being tilled for corn to be planted, wildflowers just beginning their conspicuous display, and pairs of mother-baby animals dotting each farm. It was idyllic.

Our first days riding in France were a lovely change from the starkness of the Connemara. Our bike path took us along an abandoned railway line that is now a rail-to-trail. Green and lush with a cool dampness, the riding was glorious. We were serenaded by birdsong, rode through small rural towns with cobbled streets, and the surrounding fields were just showing the first signs of summer – being tilled for corn to be planted, wildflowers just beginning their conspicuous display, and pairs of mother-baby animals dotting each farm. It was idyllic. The next day would be one of our more challenging early rides with about 600 m of elevation gain. Although not a long day, riding a bike loaded with packs uphill is much more challenging than on the flats or without the added weight. We are each carrying about 15 kg of gear (clothing, thin sleeping bag for hostels, computers, food, etc.) which adds a substantial amount of mass to our bikes. My illness made the day exceptionally challenging as I became more and more dehydrated.

The next day would be one of our more challenging early rides with about 600 m of elevation gain. Although not a long day, riding a bike loaded with packs uphill is much more challenging than on the flats or without the added weight. We are each carrying about 15 kg of gear (clothing, thin sleeping bag for hostels, computers, food, etc.) which adds a substantial amount of mass to our bikes. My illness made the day exceptionally challenging as I became more and more dehydrated. Following the Meuse River downstream, we passed through the lower Ardennes and into the Argonne – Charleville Mézières, Montherme, Stenay, and Sedan – until we finally made it to Verdun. The Maginot Line fortifications became a routine sight. Every 20 minutes or so we would pass a bunker or a pill box. Mac has always had an interest in the WWI and WWII battles so we visited Fort du Vaux, Douamont, the Tranches de Bayonets, and went to the American Cemetery. Each location was incredibly moving for us. As you ride through the area, the history is everywhere and still visible today. What was once completely barren from shelling 100 years ago, is now lush forest but you still see the craters and trenches zigzagging the forest floor. Entire towns were decimated, wiped off of the map and never to be rebuilt. These sites are now commemorated by small signs and plaques indicating where the town once existed. Markers for which battalions fought were, battle locations and their significance, and reference hill numbers are everywhere. We stopped for lunch at a bench along a canal and were perplexed that there were two flags – one French and one from the US on opposite sides of the bridge. As we explored, it was a memorial for a particular crossing which was key to forward progress during WWII. At the Tranches de Bayonets, near Verdun, WWI soldiers were buried alive by the falling dirt and debris from incessant shelling. What was supposed to give them protection ended up being their grave, only to be discovered sometime later when a villager stumbled across the bayonets sticking out of the recovering earth. The soldiers were left in place as a reminder of the brutality of war.

Following the Meuse River downstream, we passed through the lower Ardennes and into the Argonne – Charleville Mézières, Montherme, Stenay, and Sedan – until we finally made it to Verdun. The Maginot Line fortifications became a routine sight. Every 20 minutes or so we would pass a bunker or a pill box. Mac has always had an interest in the WWI and WWII battles so we visited Fort du Vaux, Douamont, the Tranches de Bayonets, and went to the American Cemetery. Each location was incredibly moving for us. As you ride through the area, the history is everywhere and still visible today. What was once completely barren from shelling 100 years ago, is now lush forest but you still see the craters and trenches zigzagging the forest floor. Entire towns were decimated, wiped off of the map and never to be rebuilt. These sites are now commemorated by small signs and plaques indicating where the town once existed. Markers for which battalions fought were, battle locations and their significance, and reference hill numbers are everywhere. We stopped for lunch at a bench along a canal and were perplexed that there were two flags – one French and one from the US on opposite sides of the bridge. As we explored, it was a memorial for a particular crossing which was key to forward progress during WWII. At the Tranches de Bayonets, near Verdun, WWI soldiers were buried alive by the falling dirt and debris from incessant shelling. What was supposed to give them protection ended up being their grave, only to be discovered sometime later when a villager stumbled across the bayonets sticking out of the recovering earth. The soldiers were left in place as a reminder of the brutality of war. We visited the Argonne cemetery, site of the last battle of WWI, on Memorial Day and were struck that each headstone had two flags – one American and one French – adorning them. Much like our visit to Margraten cemetery in the Netherlands, all immaculately kept with no signs of decay, dirt, or disrepair. In Margraten, local families adopt the graves of US soldiers and care for them as if they were one of their own, keeping it clean and bringing fresh flowers on occasion. Here the flags were placed with precision and care. It is sobering, humbling, and incredibly powerful to walk amongst the war-dead who have two flags or who have flowers placed by someone who may have never known that soldier, yet still honoring their sacrifice.

We visited the Argonne cemetery, site of the last battle of WWI, on Memorial Day and were struck that each headstone had two flags – one American and one French – adorning them. Much like our visit to Margraten cemetery in the Netherlands, all immaculately kept with no signs of decay, dirt, or disrepair. In Margraten, local families adopt the graves of US soldiers and care for them as if they were one of their own, keeping it clean and bringing fresh flowers on occasion. Here the flags were placed with precision and care. It is sobering, humbling, and incredibly powerful to walk amongst the war-dead who have two flags or who have flowers placed by someone who may have never known that soldier, yet still honoring their sacrifice. Perhaps the biggest revelation for me, though, was that everything I learned about the World Wars in high school and college was largely incomplete or without context. As we walked amongst the headstones in the cemetery, it was striking that the dates of death in Argonne were from only September to November 1918, just a 6 or 8-week period. In school, I learned that we declared war in April of 1917 and that Armistice Day was November 11, 1918, making our apparent participation in the war about 18 months. While factually correct, this is not the full story as it took almost a year to get the draft process up and running and another few months of training and moving of troops. Sure, we sent supplies, material, and money as soon as the war was declared, but the American troops didn’t actually get to the theatre until the summer of 1918. Although the US troops were not involved in the fighting for very long, their presence was critical as it provided both a much-needed morale boost and physical reinforcement for the battle-worn French troops.

Perhaps the biggest revelation for me, though, was that everything I learned about the World Wars in high school and college was largely incomplete or without context. As we walked amongst the headstones in the cemetery, it was striking that the dates of death in Argonne were from only September to November 1918, just a 6 or 8-week period. In school, I learned that we declared war in April of 1917 and that Armistice Day was November 11, 1918, making our apparent participation in the war about 18 months. While factually correct, this is not the full story as it took almost a year to get the draft process up and running and another few months of training and moving of troops. Sure, we sent supplies, material, and money as soon as the war was declared, but the American troops didn’t actually get to the theatre until the summer of 1918. Although the US troops were not involved in the fighting for very long, their presence was critical as it provided both a much-needed morale boost and physical reinforcement for the battle-worn French troops. The other thing that never really made sense was the deaths. Although more than 100,000 US military personnel died in the war effort, nearly half (45,000) died of Spanish Influenza with the vast majority of those dying before they ever reached France. This is not to trivialize the more than 70,000 direct military deaths in only a few months, but the idea that disease killed almost half of our soldiers was never emphasized in my education. Also not brought up was the fact that many countries (Serbia, Greece, Romania and the Ottoman Empire) had far more civilian deaths than military deaths. I don’t recall ever talking about this in class, ever. I’m sure there were a few sentences about how disease and famine killed many people, but the sheer scope of this is not put into a context to be fully understood.

The other thing that never really made sense was the deaths. Although more than 100,000 US military personnel died in the war effort, nearly half (45,000) died of Spanish Influenza with the vast majority of those dying before they ever reached France. This is not to trivialize the more than 70,000 direct military deaths in only a few months, but the idea that disease killed almost half of our soldiers was never emphasized in my education. Also not brought up was the fact that many countries (Serbia, Greece, Romania and the Ottoman Empire) had far more civilian deaths than military deaths. I don’t recall ever talking about this in class, ever. I’m sure there were a few sentences about how disease and famine killed many people, but the sheer scope of this is not put into a context to be fully understood. This knowledge is one of the aspects which makes traveling and seeing things first hand extremely thought-provoking. In school we learn the overly-simplified bullet points of World War I: start and end dates, was provoked by the sinking of the Lusitania, more than 100,000 US soldiers died, etc., all without a context or interpretation of the meaning of that war. Knowing that we lost a total of more than 100,000 US soldiers is chilling, but the fact that Russia lost more than four times that number of civilians as a direct result of military action and eight times that because of famine and disease was never discussed. Similarly, Germany suffered 2 million military deaths and 700,000 civilian deaths as a result of the conflict. We lost 100k, they lost millions. These different perspectives on the cost of war were never emphasized or even talked about, really. If it weren’t for travel, I would never have known.

This knowledge is one of the aspects which makes traveling and seeing things first hand extremely thought-provoking. In school we learn the overly-simplified bullet points of World War I: start and end dates, was provoked by the sinking of the Lusitania, more than 100,000 US soldiers died, etc., all without a context or interpretation of the meaning of that war. Knowing that we lost a total of more than 100,000 US soldiers is chilling, but the fact that Russia lost more than four times that number of civilians as a direct result of military action and eight times that because of famine and disease was never discussed. Similarly, Germany suffered 2 million military deaths and 700,000 civilian deaths as a result of the conflict. We lost 100k, they lost millions. These different perspectives on the cost of war were never emphasized or even talked about, really. If it weren’t for travel, I would never have known. After being humbled by the death and destruction of Verdun and the Argonne, our time in Strasbourg was a wonderful, healing time. Although terribly touristy, the town itself is engaging. We spent a few days here on our first bike trip down the Rhine River in 2014 and wanted to come back to spend a bit more time. It was the longest layover we had planned and came at a very good time. I was able to get the upper hand on my infection and, although more than 10 lbs lighter, started eating again. We had a slow visit like our time in Glasgow – one or two sights per day and a little bit of time to catch up on life. It was great.

After being humbled by the death and destruction of Verdun and the Argonne, our time in Strasbourg was a wonderful, healing time. Although terribly touristy, the town itself is engaging. We spent a few days here on our first bike trip down the Rhine River in 2014 and wanted to come back to spend a bit more time. It was the longest layover we had planned and came at a very good time. I was able to get the upper hand on my infection and, although more than 10 lbs lighter, started eating again. We had a slow visit like our time in Glasgow – one or two sights per day and a little bit of time to catch up on life. It was great.

Sometimes everything goes your way, sometimes it doesn’t. We knew going into it that the weather in Ireland in May can be unsettled. It can be a fabulously beautiful time with the most spring colors across the Emerald Isle or it can be cold, wet and miserable. After our amazing good fortune for weather in Scotland, we were hesitant to believe that our luck could hold out. Fortunately for us, we were blessed with extremely good weather for the entirety of our biking trip through Ireland. It must be the luck of the Irish which smiled down upon us.

Sometimes everything goes your way, sometimes it doesn’t. We knew going into it that the weather in Ireland in May can be unsettled. It can be a fabulously beautiful time with the most spring colors across the Emerald Isle or it can be cold, wet and miserable. After our amazing good fortune for weather in Scotland, we were hesitant to believe that our luck could hold out. Fortunately for us, we were blessed with extremely good weather for the entirety of our biking trip through Ireland. It must be the luck of the Irish which smiled down upon us. We left Glasgow on a picture perfect day – sunny but with big puffy clouds, throngs of walkers (about 40,000 of them) mostly dressed in kilts for the Kiltwalk, a charity walk to Loch Lomond, gathered on the green in front of our flat as we started our ride and a sense that spring had finally come in to full swing. The energy and pageantry of the walkers set us off on a good note. The day was not too long – about 65km (40 miles) with only one significant hill – and almost fully on bike paths. Along the way, we passed through some folks on an organized bike race, met up with other cyclists enjoying the beautiful weather, and basically sailed to our destination feeling like we could do anything. We stopped for ice cream in the early afternoon, found our way to our AirBnB without difficulty, and had an amazing and very funny dinner in town that evening. It is the kind of feeling that is hard to describe because everything simply clicked in to place as if the world was telling us that this is what we should be doing. It was an energizing and auspicious beginning.

We left Glasgow on a picture perfect day – sunny but with big puffy clouds, throngs of walkers (about 40,000 of them) mostly dressed in kilts for the Kiltwalk, a charity walk to Loch Lomond, gathered on the green in front of our flat as we started our ride and a sense that spring had finally come in to full swing. The energy and pageantry of the walkers set us off on a good note. The day was not too long – about 65km (40 miles) with only one significant hill – and almost fully on bike paths. Along the way, we passed through some folks on an organized bike race, met up with other cyclists enjoying the beautiful weather, and basically sailed to our destination feeling like we could do anything. We stopped for ice cream in the early afternoon, found our way to our AirBnB without difficulty, and had an amazing and very funny dinner in town that evening. It is the kind of feeling that is hard to describe because everything simply clicked in to place as if the world was telling us that this is what we should be doing. It was an energizing and auspicious beginning. The next few days, however, were a bit more complicated – Mac slept awkwardly the first night and woke up the next morning with a very crookneck, so much so he couldn’t move his head at all much less bike the second 60 km. This necessitated a change in plans as we had a ferry scheduled for the following day so we hopped a train to the closest town to the port which cut down our mileage considerably. We then took a ferry to Belfast and another train to get to Dublin.

The next few days, however, were a bit more complicated – Mac slept awkwardly the first night and woke up the next morning with a very crookneck, so much so he couldn’t move his head at all much less bike the second 60 km. This necessitated a change in plans as we had a ferry scheduled for the following day so we hopped a train to the closest town to the port which cut down our mileage considerably. We then took a ferry to Belfast and another train to get to Dublin. Moving bikes on and off the ferries and trains is always stressful because, much like land border crossings in Africa, each one is slightly different and everyone expects that you will know how things operate on this specific train/ferry. Unfortunately for visitors like us, each one is unique and likely not at all the same as the previous ones you have done. For example, on some trains you simply roll your bike on, panniers still attached, and strap them to the side of the train car in the wheelchair or luggage sections. This is by far the easiest yet least frequent method we have found – but oh do we love it when it happens! On other trains, you have to take the bags off and put them by your seat but hang up the bikes in specifically designated areas. Sometimes there is only one bike per area, sometimes two, sometimes four and sometimes 20, but the thing is that no one can tell you ahead of time, so you have to figure it out while jostling for space with everyone else who is boarding the train…and we have four bikes and 12 bags to negotiate. Once inside, how you place the bikes is different – sometimes you hang them up with the back wheel up, sometimes with the front wheel up, sometimes they are on an angle, sometimes they are in little individual stalls. It is a lesson in going with the flow of how things are done where you are, not how you think they should be or how you’ve done them in the past.

Moving bikes on and off the ferries and trains is always stressful because, much like land border crossings in Africa, each one is slightly different and everyone expects that you will know how things operate on this specific train/ferry. Unfortunately for visitors like us, each one is unique and likely not at all the same as the previous ones you have done. For example, on some trains you simply roll your bike on, panniers still attached, and strap them to the side of the train car in the wheelchair or luggage sections. This is by far the easiest yet least frequent method we have found – but oh do we love it when it happens! On other trains, you have to take the bags off and put them by your seat but hang up the bikes in specifically designated areas. Sometimes there is only one bike per area, sometimes two, sometimes four and sometimes 20, but the thing is that no one can tell you ahead of time, so you have to figure it out while jostling for space with everyone else who is boarding the train…and we have four bikes and 12 bags to negotiate. Once inside, how you place the bikes is different – sometimes you hang them up with the back wheel up, sometimes with the front wheel up, sometimes they are on an angle, sometimes they are in little individual stalls. It is a lesson in going with the flow of how things are done where you are, not how you think they should be or how you’ve done them in the past. Similarly, with the ferries, sometimes they simply roll them on the deck of the boat and carry your bags to your seat or cabin as luggage. Other times, especially on larger ferries, you roll on with the cars and trucks. There may be a bike rack to park in if you are lucky. If not, you wait around until someone shows you where to go. We’ve had the bikes stored in the wheelhouse of a small ferry in the Aran Islands, in an engineering room of a larger ferry to Belfast, and on a formal bike rack alongside the cars going to France. Flexibility is key as is being patient, and humble. When I was fully scolded by the Swiss train conductor for putting two bikes where there was only supposed to be one and thus somewhat blocking the path, I had to apologize profusely as he wagged his finger disapprovingly at me eventually helping me solve the problem by showing me where I could put the second bike. The thing is that arguing with or getting upset by his castigation would only have made the situation more tense. With this kind of travel, it is better to be kind and gentle even if you are boiling inside for you are a guest in their country and not just representing yourself, but your entire country. In the end, everything will be fine – the bikes get loaded and we reach our destination.

Similarly, with the ferries, sometimes they simply roll them on the deck of the boat and carry your bags to your seat or cabin as luggage. Other times, especially on larger ferries, you roll on with the cars and trucks. There may be a bike rack to park in if you are lucky. If not, you wait around until someone shows you where to go. We’ve had the bikes stored in the wheelhouse of a small ferry in the Aran Islands, in an engineering room of a larger ferry to Belfast, and on a formal bike rack alongside the cars going to France. Flexibility is key as is being patient, and humble. When I was fully scolded by the Swiss train conductor for putting two bikes where there was only supposed to be one and thus somewhat blocking the path, I had to apologize profusely as he wagged his finger disapprovingly at me eventually helping me solve the problem by showing me where I could put the second bike. The thing is that arguing with or getting upset by his castigation would only have made the situation more tense. With this kind of travel, it is better to be kind and gentle even if you are boiling inside for you are a guest in their country and not just representing yourself, but your entire country. In the end, everything will be fine – the bikes get loaded and we reach our destination. With the majority of our transportation hassles behind us, we enjoyed a couple days in Dublin listening to pub music, enjoying the big city vibe, and doing our last-minute planning. Ireland is a big island with varied and diverse terrain. One could easily spend an entire summer biking across the countryside, but realistically we could only spend about two or three weeks if we were going to also do the European areas we wanted to see as well. This meant we had to choose just one area for our bike ride. Friends we met hiking in Scotland last year, Lee and Lisa from

With the majority of our transportation hassles behind us, we enjoyed a couple days in Dublin listening to pub music, enjoying the big city vibe, and doing our last-minute planning. Ireland is a big island with varied and diverse terrain. One could easily spend an entire summer biking across the countryside, but realistically we could only spend about two or three weeks if we were going to also do the European areas we wanted to see as well. This meant we had to choose just one area for our bike ride. Friends we met hiking in Scotland last year, Lee and Lisa from  We were very happy with our decision as the biking was truly dramatic, perhaps some of the most beautiful bike rides we have ever ridden. The Burren’s stark hillsides, eerily quiet road, and endless undulating terrain made us feel as if we were on a totally different continent, if not the planet. This is the area is also known for the dramatic Cliffs of Moher (Cliffs of Insanity if you are a Princess Bride fan or cliff which held the cave and lake with the locket horcrux in the 6th Harry Potter movie). We visited the Cliffs late in the evening to catch the sunset – and oh what a sunset it was!

We were very happy with our decision as the biking was truly dramatic, perhaps some of the most beautiful bike rides we have ever ridden. The Burren’s stark hillsides, eerily quiet road, and endless undulating terrain made us feel as if we were on a totally different continent, if not the planet. This is the area is also known for the dramatic Cliffs of Moher (Cliffs of Insanity if you are a Princess Bride fan or cliff which held the cave and lake with the locket horcrux in the 6th Harry Potter movie). We visited the Cliffs late in the evening to catch the sunset – and oh what a sunset it was! On the Aran Islands, our favorite place was the rarely visited Dún Dúchatair (the Black Fort). Perched on a rocky but crumbling coastal cliff, initially built more than 3,000 years ago then re-fortified just 1,000 years ago, no one is sure of what the purpose of the structures was, only that eons of storms, tsunamis and erosion have obscured the true purpose. Most tourists who visit the Aran Islands only come for a day trip, so tend to head straight to Dún Aonghasa, the larger and more developed site on the other side of the island. Because we were staying the night on the island and that Colburn and I chose to visit Dún Dúchatair late in the afternoon, there was not another soul anywhere in the area. We passed a farmer planting vegetables in the thin and rocky soil about 4 or 5 km from the entrance to the site, but no one else at all. In fact, there were barely even any paths from foot traffic anywhere in the site.

On the Aran Islands, our favorite place was the rarely visited Dún Dúchatair (the Black Fort). Perched on a rocky but crumbling coastal cliff, initially built more than 3,000 years ago then re-fortified just 1,000 years ago, no one is sure of what the purpose of the structures was, only that eons of storms, tsunamis and erosion have obscured the true purpose. Most tourists who visit the Aran Islands only come for a day trip, so tend to head straight to Dún Aonghasa, the larger and more developed site on the other side of the island. Because we were staying the night on the island and that Colburn and I chose to visit Dún Dúchatair late in the afternoon, there was not another soul anywhere in the area. We passed a farmer planting vegetables in the thin and rocky soil about 4 or 5 km from the entrance to the site, but no one else at all. In fact, there were barely even any paths from foot traffic anywhere in the site. Being there late in the afternoon as the sun was low on the western horizon, waves crashing against the steep cliffs and the salty dampness of ocean air clinging to our skin, it was easy to imagine this place as a home or an outpost 3,000 years ago. The remnants of the buildings have openings to the southeast to let in the early morning light and the stout backs designed to protect from the prevailing winds. The terraced walls of defense are 13 feet thick in some areas and are built to the very edge of a 300-foot cliff, making the area easy to defend from invaders. As with the Burren, we felt that we had been transported back in time or far, far away. It was magical.

Being there late in the afternoon as the sun was low on the western horizon, waves crashing against the steep cliffs and the salty dampness of ocean air clinging to our skin, it was easy to imagine this place as a home or an outpost 3,000 years ago. The remnants of the buildings have openings to the southeast to let in the early morning light and the stout backs designed to protect from the prevailing winds. The terraced walls of defense are 13 feet thick in some areas and are built to the very edge of a 300-foot cliff, making the area easy to defend from invaders. As with the Burren, we felt that we had been transported back in time or far, far away. It was magical. The third place we fell in love with was Doolough Valley. The scenery is stunning but the history here is heart-breaking. During the famine of 1849, many of the locals relied on relief aid from the government but the officials required that the hundreds of starving people walk 12 miles to see them at the hunting lodge where they were staying in order to reauthorize their famine aid. More than 17 people are known to have died because of the energy expenditure needed to accomplish this arduous walk – 24 miles round trip. There are memorials on the pass and also in the surrounding towns. It was very sobering to contrast our life of abundance with this level of starvation less than 200 years ago.

The third place we fell in love with was Doolough Valley. The scenery is stunning but the history here is heart-breaking. During the famine of 1849, many of the locals relied on relief aid from the government but the officials required that the hundreds of starving people walk 12 miles to see them at the hunting lodge where they were staying in order to reauthorize their famine aid. More than 17 people are known to have died because of the energy expenditure needed to accomplish this arduous walk – 24 miles round trip. There are memorials on the pass and also in the surrounding towns. It was very sobering to contrast our life of abundance with this level of starvation less than 200 years ago.

We had far too many close calls where drivers would pass us at full speed without allowing for a safe passing distance (1.5 meters in Ireland) even on the crest of a hill, blind corners and when another car was coming the other way. They simply continued in the lane as if we were not there, running one or more of us off the road more than once. After hearing of our travails, our brother-in-law sent us an idea which I think is brilliant – put a brightly colored pool noodle across the back of your bike so that it sticks out the required 1.5 meters. This gives drivers an indication of what a “safe passing distance” looks like in real life. I had a similar idea while riding but was much more passive aggressive about it – I would attach a sharp object (like broken glass) on the end so that if someone did come too close, it would scratch their car’s paint. I would consider the damage from this a natural consequence for them not respecting the required safe distance. In the end, we truly enjoyed parts of biking Ireland but would probably not do it again until there are either proper bike paths, a change of heart from drivers, or another way of assuring our safety.

We had far too many close calls where drivers would pass us at full speed without allowing for a safe passing distance (1.5 meters in Ireland) even on the crest of a hill, blind corners and when another car was coming the other way. They simply continued in the lane as if we were not there, running one or more of us off the road more than once. After hearing of our travails, our brother-in-law sent us an idea which I think is brilliant – put a brightly colored pool noodle across the back of your bike so that it sticks out the required 1.5 meters. This gives drivers an indication of what a “safe passing distance” looks like in real life. I had a similar idea while riding but was much more passive aggressive about it – I would attach a sharp object (like broken glass) on the end so that if someone did come too close, it would scratch their car’s paint. I would consider the damage from this a natural consequence for them not respecting the required safe distance. In the end, we truly enjoyed parts of biking Ireland but would probably not do it again until there are either proper bike paths, a change of heart from drivers, or another way of assuring our safety. Ending off our time in Ireland was a true treat where we were able to meet up with our friend and third child, Zara, and meet her parents for the first time. We met Zara diving in Mozambique almost two years ago and have stayed in contact with her ever since. Seeing her again in a totally different environment and meeting her parents reminded us of why we travel – in the end, it is the people you meet and the experiences you have that make traveling worthwhile. We were thoroughly spoiled by their hospitality and fell in love with Northern Ireland.

Ending off our time in Ireland was a true treat where we were able to meet up with our friend and third child, Zara, and meet her parents for the first time. We met Zara diving in Mozambique almost two years ago and have stayed in contact with her ever since. Seeing her again in a totally different environment and meeting her parents reminded us of why we travel – in the end, it is the people you meet and the experiences you have that make traveling worthwhile. We were thoroughly spoiled by their hospitality and fell in love with Northern Ireland.

The sense of time is immense, far beyond what we can comprehend coming from the US. In the little town of Cairnryan, we stayed in a 350-year-old merchant house. It was built just 40 years after the pilgrims landed in Massachusetts when the US was still forming the colonies. The home has been in continuous operation for longer than the entire history of our country but is young by Scottish standards.

The sense of time is immense, far beyond what we can comprehend coming from the US. In the little town of Cairnryan, we stayed in a 350-year-old merchant house. It was built just 40 years after the pilgrims landed in Massachusetts when the US was still forming the colonies. The home has been in continuous operation for longer than the entire history of our country but is young by Scottish standards.

The village of Skara Brae was hidden under a sand dune for millennia, only to be uncovered by a fierce storm in the late 1800s but quickly forgotten. It wasn’t until the 1910’s that anyone else came to see it. Much like Pompeii, the dunes covering the village preserved the site on an intimate level so that when you walk through it is like traveling through time. Skara Brae, however, is only one of a handful of sites of a similar age, each preserved to an amazing degree. Our favorite was Brouch of Gurness with its curving pathways, layers of homes, and a beautiful view over the water.

The village of Skara Brae was hidden under a sand dune for millennia, only to be uncovered by a fierce storm in the late 1800s but quickly forgotten. It wasn’t until the 1910’s that anyone else came to see it. Much like Pompeii, the dunes covering the village preserved the site on an intimate level so that when you walk through it is like traveling through time. Skara Brae, however, is only one of a handful of sites of a similar age, each preserved to an amazing degree. Our favorite was Brouch of Gurness with its curving pathways, layers of homes, and a beautiful view over the water.

“Are you my people? Oh, no, you’re the North Americans who signed in yesterday!”” exclaimed the wildlife ranger as we were enjoying sundowners on the second night of our self-drive through Botswana. Still confused, we asked who it was that he was looking for? “Oh, there were reservations for people who did not show up last night and I am worried. It is the rainy season and the roads aren’t good. People get in to trouble when they are stuck and I want to make sure they are safe.” He was looking for the people who were supposed to be at the camping site last night but didn’t show up. As is common in Africa, we spent the next 20-30 minutes chatting with him about travel, the rainy season, what life is like in America, and the antics of our current President. He thanked us for signing in to the register he had left at the gate as he had to leave the post to go search for the missing campers. “I don’t remember the last time we had someone from North America” he quipped “they usually go on guided safaris. The Europeans, though, especially Germans and Dutch, they come here in herds.”

“Are you my people? Oh, no, you’re the North Americans who signed in yesterday!”” exclaimed the wildlife ranger as we were enjoying sundowners on the second night of our self-drive through Botswana. Still confused, we asked who it was that he was looking for? “Oh, there were reservations for people who did not show up last night and I am worried. It is the rainy season and the roads aren’t good. People get in to trouble when they are stuck and I want to make sure they are safe.” He was looking for the people who were supposed to be at the camping site last night but didn’t show up. As is common in Africa, we spent the next 20-30 minutes chatting with him about travel, the rainy season, what life is like in America, and the antics of our current President. He thanked us for signing in to the register he had left at the gate as he had to leave the post to go search for the missing campers. “I don’t remember the last time we had someone from North America” he quipped “they usually go on guided safaris. The Europeans, though, especially Germans and Dutch, they come here in herds.”

By the end of our trip, our kids will have spent 13 weeks doing wildlife research and conservation volunteering in Africa. If you include the community volunteering, it rises to 18 weeks. This struck me when we were working with a college intern doing a 12-week assignment cataloging wild dog pack dynamics in northern Namibia. Our kids will have spent more time in the field than a college semester requires for a full-time internship. Not a bad way for a 7th and 9th grade student to learn about biology, ecology, botany, zoology and a myriad of other topics.

By the end of our trip, our kids will have spent 13 weeks doing wildlife research and conservation volunteering in Africa. If you include the community volunteering, it rises to 18 weeks. This struck me when we were working with a college intern doing a 12-week assignment cataloging wild dog pack dynamics in northern Namibia. Our kids will have spent more time in the field than a college semester requires for a full-time internship. Not a bad way for a 7th and 9th grade student to learn about biology, ecology, botany, zoology and a myriad of other topics.

Because humans and chimps share 97% of the same DNA, Sheila was able to apply her nursing knowledge to help Pal recover. Once he was better, Pal needed a new home as he had become human habituated so could not be released back in to the wild. David, Sheila’s husband, built an enclosure so that the chimp would have room to play and explore. As word spread of Pal’s recovery and the care David and Sheila provided, more people would bring chimps and other wildlife in need to the couple. They always welcomed new animals in and released them back to the wild when possible but also provide a long-term home for those which cannot be released.

Because humans and chimps share 97% of the same DNA, Sheila was able to apply her nursing knowledge to help Pal recover. Once he was better, Pal needed a new home as he had become human habituated so could not be released back in to the wild. David, Sheila’s husband, built an enclosure so that the chimp would have room to play and explore. As word spread of Pal’s recovery and the care David and Sheila provided, more people would bring chimps and other wildlife in need to the couple. They always welcomed new animals in and released them back to the wild when possible but also provide a long-term home for those which cannot be released.

Each of the chimps had a horrendous story about how they came to be part of the rescue network; one had been a pet for a family in South Sudan but had become so unruly (as chimps do when they enter their teen years) that the family simply abandoned it on a street, another had been tied to a platform outside of a restaurant in the Central African Republic as an living advertisement, yet another had been hidden by villagers as they fled from rebels in the Democratic Republic of Congo knowing that she would be killed and eaten as bush-meat if found. Each story is a little more heartbreaking than the previous. But through a network of concerned individuals, these six chimps had been kept safe until they were approved to come to the sanctuary.

Each of the chimps had a horrendous story about how they came to be part of the rescue network; one had been a pet for a family in South Sudan but had become so unruly (as chimps do when they enter their teen years) that the family simply abandoned it on a street, another had been tied to a platform outside of a restaurant in the Central African Republic as an living advertisement, yet another had been hidden by villagers as they fled from rebels in the Democratic Republic of Congo knowing that she would be killed and eaten as bush-meat if found. Each story is a little more heartbreaking than the previous. But through a network of concerned individuals, these six chimps had been kept safe until they were approved to come to the sanctuary.

As volunteers, we spent several days prepping for the new arrivals; cleaning out old quarantine enclosures which had been reclaimed by the vegetation because they sat unused for more than a decade, chopping and hauling trees and vines to put inside the enclosures for the chimps to play and climb on, harvesting bedding so they would have a warm and comfortable place to sleep, making a tire swing, etc.

As volunteers, we spent several days prepping for the new arrivals; cleaning out old quarantine enclosures which had been reclaimed by the vegetation because they sat unused for more than a decade, chopping and hauling trees and vines to put inside the enclosures for the chimps to play and climb on, harvesting bedding so they would have a warm and comfortable place to sleep, making a tire swing, etc.  On the night of the arrival, we were allowed to observe the process. Thalita Calvi, the sanctuary vet, had briefed us ahead of time that the chimps had spent more than three days in transit crates because of a bureaucratic delay. They would likely be tired, hungry and extremely frightened. Even happy chimps are amazingly strong for their size but when they are frightened, their power is even more impressive which meant that we should stay far back from the scene and simply watch the work being done.

On the night of the arrival, we were allowed to observe the process. Thalita Calvi, the sanctuary vet, had briefed us ahead of time that the chimps had spent more than three days in transit crates because of a bureaucratic delay. They would likely be tired, hungry and extremely frightened. Even happy chimps are amazingly strong for their size but when they are frightened, their power is even more impressive which meant that we should stay far back from the scene and simply watch the work being done. However, like Eisenhower once said, “while planning is indispensable, plans are useless”. Flight delays meant that the chimps didn’t arrive at the sanctuary until after dark. As the trucks pulled in, there were no outside lights to illuminate the unloading area or path to the enclosures but we had headlamps and flashlights with us so moved closer to light up the area as best we could. The chimps were transferred in dog crates so were easy to move but needed more hands to make sure that no chimps were left behind alone in the dark.

However, like Eisenhower once said, “while planning is indispensable, plans are useless”. Flight delays meant that the chimps didn’t arrive at the sanctuary until after dark. As the trucks pulled in, there were no outside lights to illuminate the unloading area or path to the enclosures but we had headlamps and flashlights with us so moved closer to light up the area as best we could. The chimps were transferred in dog crates so were easy to move but needed more hands to make sure that no chimps were left behind alone in the dark. It was a busy and emotional time for all; one chimp reached his hand out between the bars simply wanting someone, anyone, to comfort him. I held his hand for a few minutes while he settled. Another chimp tried to escape but quickly clambered up on one of the handlers when the handler made a chimp comforting sound. A third chimp clung to the vet as she moved between enclosures making sure that all of the chimps were settled with the right partners. When it was all done, someone said, “You’re safe now, you’re home now, you’ll never be in danger again.” It is true, they have found their forever home and once cleared from quarantine, will get to become part of a larger family group. It felt good to be able to help.

It was a busy and emotional time for all; one chimp reached his hand out between the bars simply wanting someone, anyone, to comfort him. I held his hand for a few minutes while he settled. Another chimp tried to escape but quickly clambered up on one of the handlers when the handler made a chimp comforting sound. A third chimp clung to the vet as she moved between enclosures making sure that all of the chimps were settled with the right partners. When it was all done, someone said, “You’re safe now, you’re home now, you’ll never be in danger again.” It is true, they have found their forever home and once cleared from quarantine, will get to become part of a larger family group. It felt good to be able to help.

Without the ability to do x-rays or lab work in the field, it was impossible to determine the extent of his internal injuries. There were several obvious wounds visible externally which would account for some but not all of the blood loss. The vet needed to anesthetize the chimp to examine him and stitch up what she could of the injuries, but without a formal surgery and recovery to use, all of it must be done in one of the feeding enclosures as it is the only space where the chimps can be safely separated from each other. All of the volunteers assisted in different ways; monitoring vital signs, opening and cleaning supplies, running errands for things like hot water bottles or more medication, etc. The vet had an infected wound on her hand and wasn’t sure how much she would be able to use it so I gloved up to help where I could. After three and a half hours, as much as could be done to patch him back together had been done. He was slow to come out of the anesthesia and never fully recovered, dying from his injuries the next day.

Without the ability to do x-rays or lab work in the field, it was impossible to determine the extent of his internal injuries. There were several obvious wounds visible externally which would account for some but not all of the blood loss. The vet needed to anesthetize the chimp to examine him and stitch up what she could of the injuries, but without a formal surgery and recovery to use, all of it must be done in one of the feeding enclosures as it is the only space where the chimps can be safely separated from each other. All of the volunteers assisted in different ways; monitoring vital signs, opening and cleaning supplies, running errands for things like hot water bottles or more medication, etc. The vet had an infected wound on her hand and wasn’t sure how much she would be able to use it so I gloved up to help where I could. After three and a half hours, as much as could be done to patch him back together had been done. He was slow to come out of the anesthesia and never fully recovered, dying from his injuries the next day.

Please note that much of the following description of our time in Rwanda may be very disturbing if you are not familiar with the Rwandan Genocide. We absolutely enjoyed Rwanda, but the history is full of pain.

Please note that much of the following description of our time in Rwanda may be very disturbing if you are not familiar with the Rwandan Genocide. We absolutely enjoyed Rwanda, but the history is full of pain.

As we passed through no-man’s land, we all girded ourselves for the same experience entering Uganda. We were more than a little surprised by the lack of fixers when we parked outside of the immigration hall. It was the first time that we have not been swarmed by money changers and fixers as soon as we pulled up, in fact there was not one to be seen – definitely a welcome change. In contrast to the grumpy affect we experienced from start to finish in Kenya, the Ugandan officials were smiling kindly and eager to help us get through the required paperwork and directing us to where we needed to go next. It was organized and everything you need (foreign exchange, ATM, bank, etc.) is in one building. No wonder there were no fixers – there was no need!

As we passed through no-man’s land, we all girded ourselves for the same experience entering Uganda. We were more than a little surprised by the lack of fixers when we parked outside of the immigration hall. It was the first time that we have not been swarmed by money changers and fixers as soon as we pulled up, in fact there was not one to be seen – definitely a welcome change. In contrast to the grumpy affect we experienced from start to finish in Kenya, the Ugandan officials were smiling kindly and eager to help us get through the required paperwork and directing us to where we needed to go next. It was organized and everything you need (foreign exchange, ATM, bank, etc.) is in one building. No wonder there were no fixers – there was no need!

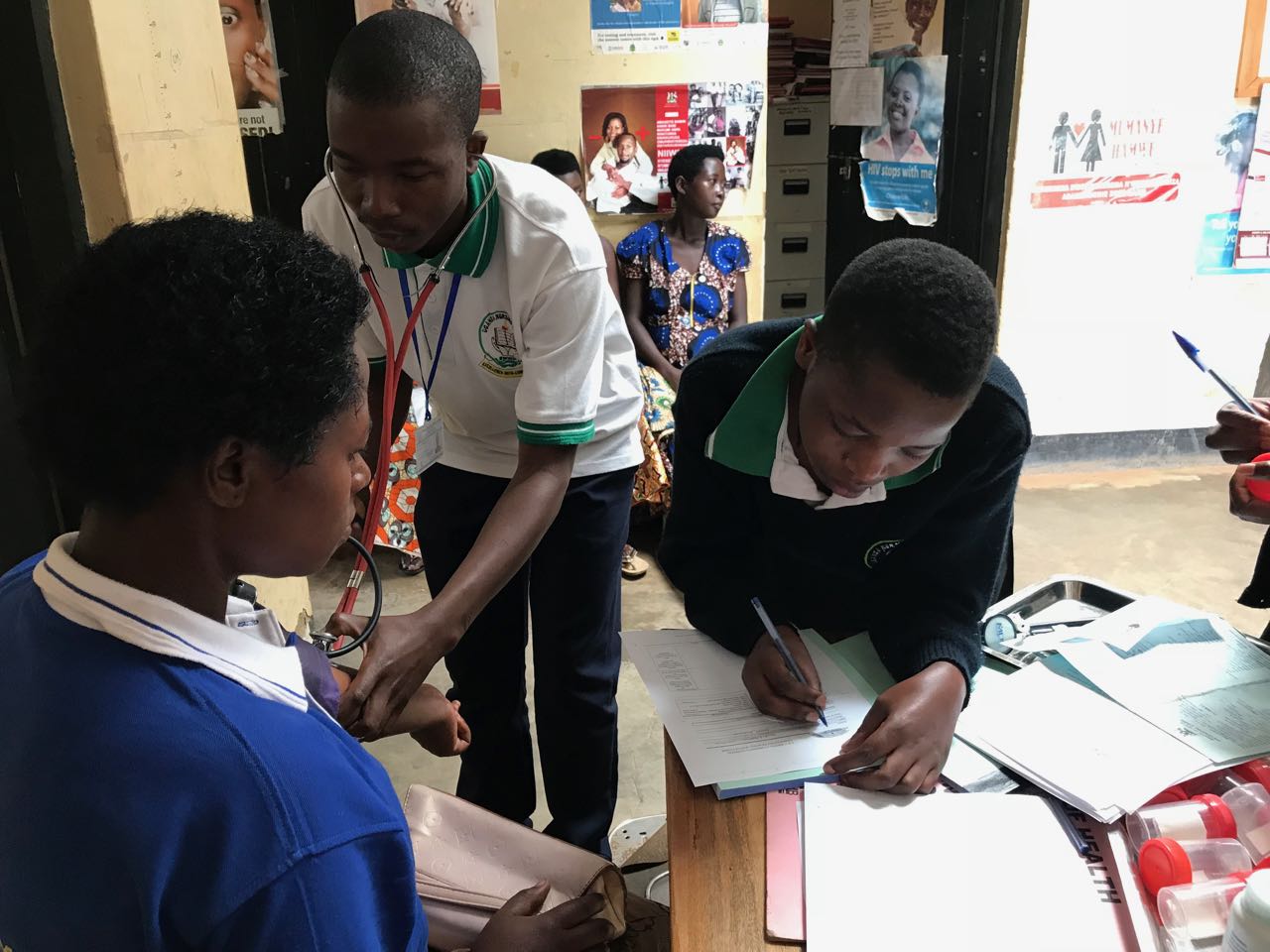

Leaving the open plains of Queen Elizabeth Park behind, we headed to the cool mountains of Bwindi Impenetrable Forest for some volunteering for the local nursing school that I learned about many years ago and work with the Batwa Development Program. Colburn and the kids had decided to raise money to build a permanent home for a Batwa family who has been living in temporary structures. The “Build a Batwa Home” is a partnership between the local community and the Kellermann Foundation.

Leaving the open plains of Queen Elizabeth Park behind, we headed to the cool mountains of Bwindi Impenetrable Forest for some volunteering for the local nursing school that I learned about many years ago and work with the Batwa Development Program. Colburn and the kids had decided to raise money to build a permanent home for a Batwa family who has been living in temporary structures. The “Build a Batwa Home” is a partnership between the local community and the Kellermann Foundation.

When we arrived, the Principal mentioned that she and the faculty were very eager to learn about how to use more engaging methods of teaching so I did a series of workshops for the faculty. Fortuitously, they were also working on the design of a new skills lab so I was able sit in on those discussions as well. The experience was exactly what I had been hoping for all along – I was able to volunteer my professional experience to help a nursing school. The relationship is one which could become a long-term engagement as the process of changing instruction takes time and intermittent periodic reinforcement. We all loved Bwindi and the community there so hope to come back soon.

When we arrived, the Principal mentioned that she and the faculty were very eager to learn about how to use more engaging methods of teaching so I did a series of workshops for the faculty. Fortuitously, they were also working on the design of a new skills lab so I was able sit in on those discussions as well. The experience was exactly what I had been hoping for all along – I was able to volunteer my professional experience to help a nursing school. The relationship is one which could become a long-term engagement as the process of changing instruction takes time and intermittent periodic reinforcement. We all loved Bwindi and the community there so hope to come back soon.